Lessons from Meghalaya – Carmo Noronha – Bethany Society

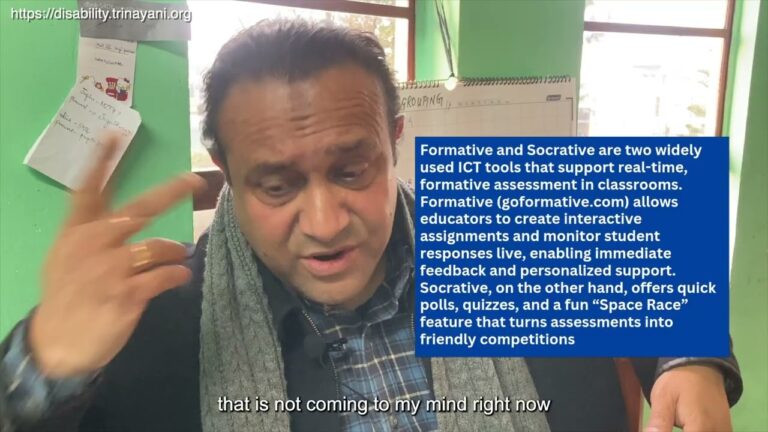

In this film, Dr. Carmo Noronha, Secretary of Bethany Society, reflects on over three decades of transformative work done in Meghalaya. He shares the journey from segregated education to inclusive classrooms, discusses the power of community-based rehabilitation, the importance of parental involvement, and the impact of inclusive education. His insights offer a vision of a world where every individual, regardless of ability, has the opportunity to thrive. This film is a must-watch for anyone passionate about education and social change!

You can navigate to the specific topics using the following chapters:

00:00 – Ritika Sahni’s introduction to the film

00:33 – Carmo on Bethany Society

03:47 – What steps have you taken to support or enhance education for children with disabilities?

09:41 – In your view, what are the essential elements that constitute quality education?

12:26 – What further steps do you believe can be taken to advance progress in disability-inclusion?

Dive Deeper: More on Disability

Learn about the most common inquiries surrounding disability, education, legislation, accessibility, employment and other sectors related to disability.

Playlist

Access & Inclusion

Playlist

Adaptive Sports

Playlist

Alternative Communication Methods

Playlist

Autism & Neurodiversity

Playlist

Blindness & Adaptations

Playlist